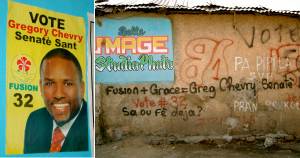

Having set up GPS in Saint Raphael and Hinche, we have finally made it to Mirebalais, the last location where our team needs to make measurements north of PaP. Of course we still have to retreat back north to pick up the instruments we have left behind, but the finish line is in sight. We arrived in Mireabalais last night and are spending a day here allowing the data to accumulate. Mireabalais is a town of 12,000 with another 50,000 in the surrounding rural areas. In many ways it is a microcosm of the Haiti we have grown to know in our 2 weeks in the north. As we approach the town, small stone houses begin to appear along the rocky, dirt roads and people, lots of people are walking in the streets, riding motorcycle taxis, and just hanging out. It is dusty, lots of garbage, and the river we cross is polluted. Life here in this town is tough and I am not overjoyed to be arriving. But then we approach the town square and enter a different universe. There are thousands of people, and they are singing, and they are rejoicing. People are smiling, vendors are selling all kinds of food, and its just one big party. As we pull up to the curve, a little girl, the daughter of a vendor selling sausages, gives us that shy but inquisitive look with just a hint of a smile, which beams oh so much brighter when Sarah offers her a lollipop. This is a community; a close knit group of neighbors that seem oblivious to the hardships that is their daily ritual. We are told that they have been celebrating life every night for 15 straight nights. I continue to be amazed, but the simple fact is that Haitians embrace life and look forward to the future despite what my culture might view as difficult circumstances and dim prospects. The spirit of the Haitian people is amazing and I am humbled.

After breakfast the next day, we get a flat tire repaired (another casualty of the tough roads) and head out to the local high school, unannounced, to see if we can talk to the students about earthquakes. Despite the fact that they are taking exams, the principal is keen for us to talk with them. As a teacher, I am not thrilled with interrupting an exam and suggest that they should each be given a few extra points, to which we hear many “Oui! Oui!” It is again great to talk with the students and hear their concerns and answer their questions. Mirebalais is far enough from PaP that they suffered no damage, but they did feel the earthquake roll by. Many questions focused, as usual, on whether it is safe to be outside in a quake (yes, very), and what to do if inside (get out), and what to do if they can’t get out (get near a strong support structure or under a strong desk).

Teaching about earthquakes to students at Mirebalais' high school.

Later in the day we meet Sammy, a very personable Haitian living in Boston but back here visiting, and his uncle Greg (also very personable), who is a former military officer who spent time training in Georgia, who now owns several local businesses, and who cares deeply for his community and his country. Greg is currently housing more than a dozen of more than 100 PaP college students who are now refugees in this town, as their school and their homes were destroyed in the earthquake. He introduces us to the students and as a group we talk about their experience in PaP, earthquakes, and the future. Their stories are tragic, they have lost many friends, teachers, and family members, and they are concerned with how they will be able to continue their education. Greg and several other people with means are in the planning stages of a new technical college they will try and build here, as a new home to these and other displaced students. I have promised to bring word of their situation to my colleagues and institution to see how may be able to help and Sarah introduced them to the organization Teachers Without Borders (see blog below), as it is likely they will take a great interest. We learn so much from these students about what happened on Jan 12, with one disturbing piece of information that particularly stands out. It turns out that culturally, Haitians have been taught to seek shelter indoors in case of any type of emergency. And many, many of their friends and family members who were outside when the earthquake struck, ran indoors and were then killed when the buildings collapsed. We are stunned. It’s a tragedy within a tragedy.

Talking with college students from PaP that are now refugees in Mireabalias.

Our proactive effort to educate the Haitian population has taken on even more urgency with this new information. And as has happened several times in the past 2 weeks, we are quickly given another great opportunity to educate. We are again invited to go live on the radio the next morning, and this time they are taping the show and planning on distributing it throughout Haiti. With Sammy interpreting for us this time, and the local DJ Tenior (a very bright fellow who had read our 2008 paper and had been warning his listeners about the dangers of an earthquake – WOW!; apparently they all thought he was crazy) asking a series of questions, we spent about 45 minutes talking about earthquakes, what happened on Jan 12, what we know and don’t know about future seismic activity in Haiti, tsunamis dangers in the north and what to do to survive one, and most of all: if you feel shaking and if at all possible, get out of any building and stay out.

Live on the radio in Mirebalais. Tenior (standing) conducted the interview, while Sammy (sitting) translated between English and Creole.

Before leaving town after the radio interview, I stand in the back of our pickup truck to watch thousands from this town gather again, this time in the morning. It is February 12, exactly one month after the earthquake, and it is the first of 3 days of national mourning. The people are praying and they are singing, they are a thriving community. As I turn to leave, a little boy, perhaps 8, says to me “Mister, good morning, how are you?” with a big smile only matched by his fathers. “I am fine, how are you?” “My name is Tony.” “My name is Andy and it is very nice to meet you.” He finishes with “Have a nice day”, which I think perhaps exhausts his English, but not his friendliness.

The town of Mirebalais gathers on February 12, one month after the earthquake, for the first of 3 days of national mourning (click to enlarge).

Andy